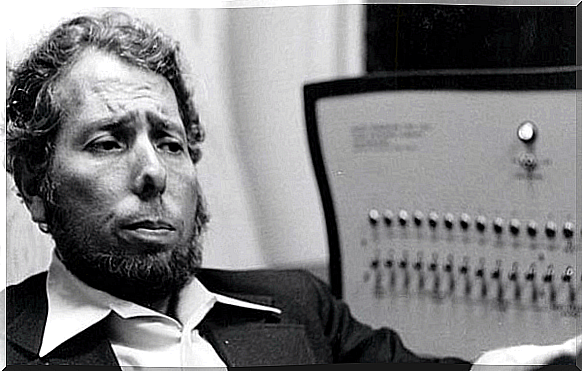

Milgram’s Experiment: Blind Obedience

Why does a person obey? How far can he follow an order that goes against his morality? These and other questions can perhaps be solved by Milgram’s experiment (1963) or at least that was the intention of this psychologist.

It is one of the most famous experiments in the history of psychology and also the most important for its development. The conclusions reached, in fact, were of fundamental importance to change the idea of human being that one had up to that moment. In particular, it allowed us to understand why good people can, on some occasions, be very cruel. Are you ready to learn about the Milgram experiment?

Milgram’s experiment on blind obedience

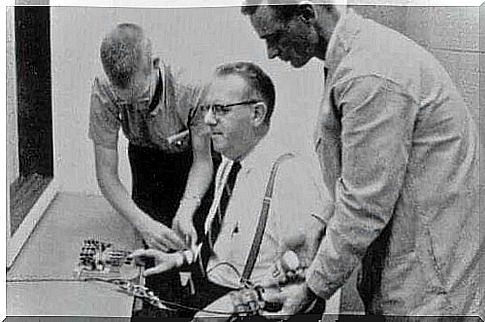

Before discussing obedience, we will talk about how the Milgram experiment was carried out. First of all, Milgram ran an ad in the newspaper in which she was looking for paid participants for a psychological research. When the subjects showed up in the Yale University laboratory, they were told they would participate in learning research .

They would have had to ask another individual a few questions on a word list to evaluate their memory. However…

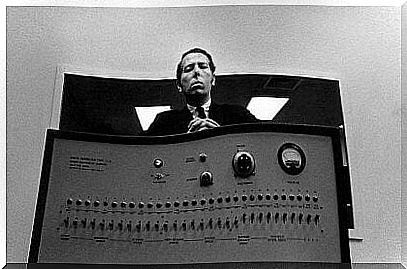

In reality, this situation was a staging that hid the real experiment. The participant thought he was asking questions of another participant who, in fact, was an accomplice of the researcher. Questions had to be asked about a list of words that the latter had previously memorized. If he guessed right, he moved on to the next word; if he was wrong, the subject had to give an electric shock to the accomplice of the researcher (in reality no shock was applied, but the subject was convinced so).

It was also explained that the machine used for such electrical discharges had 30 levels of intensity. With each mistake they made, the person had to increase the strength of the shock by one level. Before starting the experiment, small shocks were applied to the accomplice who pretended to feel pain.

At the beginning of the experiment, the accomplice answered the questions correctly and without hesitation. A As you experiment progressed, she began to make mistakes and the subject had therefore applicargli shocks. The behavior that the accomplice had to carry out was the following: once he reached level 10 of intensity, he would have to start complaining about the experiment and wanting to abandon it; at level 15 of the experiment, he should have refused to answer questions and show his opposition to the experiment with determination; once he reached level 20 in intensity, he would have to pretend he was unconscious and, consequently, the ability to answer questions.

All the while, the researcher asked the subject to continue the test; even when the accomplice had, for all intents and purposes, fainted, since the lack of an answer was regarded as a mistake. In order for the subject not to succumb to the temptation to abandon the experiment, the researcher reminded him that he had committed himself to reaching the end and that any responsibility deriving from what could have happened was his, the researcher.

How many people do you think have made it to the last level of intensity (a level of electrical discharge that could have caused even death)? How many people stopped when the accomplice passed out? Well, let’s proceed with the results of these “obedient criminals”.

Results of the Milgram experiment

Before carrying out the experiments, Milgram asked some fellow psychiatrists to predict the results. Psychiatrists thought that most subjects would abandon the experiment at the first complaint from the accomplice; that about 4% would have reached the level at which loss of consciousness was simulated and that only a few pathological cases, one in a thousand, would have reached the maximum (Milgram, 1974).

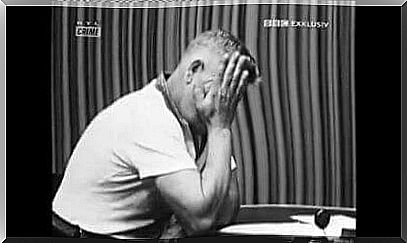

These predictions were completely erroneous: the experiments showed unexpected results . Of the 40 subjects in the first experiment, 25 made it to the end. On the other hand, about 90% of the participants had the accomplice unconscious (Milgram, 1974). The participants completely obeyed the researcher; although some of them showed very high levels of stress and rejection, they still continued to obey.

Some argued that Milgram’s experiment could give biased results, but the study was replicated several times, with different types of tests and designs, which can be found in Milgram’s book (2016), and all led to very similar results. . Even a researcher from Munich obtained shocking results: 85% of the subjects reached the maximum level of electric shock (Milgram, 2005).

Shanab (1978) and Smith (1998) in their studies show us that the results are generalizable to any country of Western culture. Despite this, we must be careful when we think that this is a universal social behavior: trans-cultural research does not guarantee overwhelming and definitive results.

Conclusions from the Milgram experiment

Once confronted with these results, the first question we ask ourselves is: why do people obey to such a degree? In Milgram (2016) multiple transcripts of the conversations between subjects and the scholar are reported. We can observe that the majority of the subjects were badly engaging in this behavior, so it cannot have been cruelty that moved them. It may be that the answer lies in the “authority” of the researcher, the one to whom the subjects actually attribute responsibility for everything that happens.

Through variations to the Milgram experiment, a number of factors of particular influence for obedience were understood:

- The role of the researcher: the presence of a researcher wearing a lab coat causes subjects to attribute to him an authority associated with his professionalism and, for this reason, are more obedient to his requests.

- Perceived responsibility: it is the responsibility that the subject believes he has over his actions. When the researcher tells him that he is in charge of the experiment, the subject sees his responsibility diminish and it is easier for him to obey.

- Awareness of a hierarchy: subjects who had a strong sense of hierarchy came to see themselves above the accomplice and below the researcher; therefore they gave more importance to the orders of their “boss” rather than to the well-being of the accomplice.

- The sense of commitment: the fact that the participants had committed themselves to carry out the experiment made it impossible for them, to a certain extent, to oppose it.

- The breakdown of empathy: when the situation forces the depersonalization of the accomplice, we see how the subjects lose empathy towards him and it is easier for them to prefer obedience.

These factors alone do not lead one person to blindly obey another, but the sum of them generates a situation in which obedience becomes very likely, regardless of the consequences. Milgram’s experiment provides us with a further example of the strength of the situation mentioned by Zimbardo (2012). If we are aware of the strength of our context, this can lead us to behave differently from our principles.

People obey blindly since the pressure of the factors mentioned outweighs the pressure that personal conscience can exert. This helps us to explain many historical events, such as the great support enjoyed by the fascist dictatorships of the last century or more concrete events, such as the behavior and explanations of the doctors who contributed to the extermination of Jews during World War II. , on the occasion of the Nuremberg Trials.

The sense of obedience

Whenever we see behaviors that do not confirm our expectations, it is interesting to ask ourselves what the cause is. Psychology gives us a very interesting explanation of obedience. It is based on the fact that the decision taken by a competent authority with the intention of favoring the group has more adaptive consequences than when the decision is the product of a discussion that involves the whole group.

Imagine a society that is run by an authority that is never questioned, rather than a society where any authority is brought to trial. Having no control mechanism, logically, the former will be much faster than the latter in the execution of the decisions taken : a very important variable that can determine victory or defeat in a conflict situation. This is also closely related to Tajfel’s (1974) social identity theory, for more information here.

At this point, what can we do in the face of blind obedience? It may be that authority and hierarchy are adaptive in certain contexts, but this does not legitimize blind obedience to immoral authority. And this is where a problem comes in: if we get a society in which any authority is questioned, we will have a healthy and just community that will collapse in the face of other societies with which it will come into conflict, due to its slowness in taking decisions.

On an individual level, if we are to avoid falling into blind obedience, it is important to keep in mind that all of us can sometimes succumb to the pressures of the situation. For this same reason, the best thing we can do in these cases is to take into consideration the way in which contextual factors affect us; therefore, when these overwhelm us, we can try to regain control and not delegate, however great the temptation, a responsibility that belongs to us.

Experiments like this help us reflect on the nature of the human being. They allow us to see that dogmas, such as that the human being is good or bad, are very far from explaining our reality. It is necessary to shed light on the complexity of human conduct in order to be able to understand the reasons for it. Deepening this aspect will help us to understand our history and not to repeat certain actions.

References:

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 67, 371-378.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to Authority: An Experimental Look. New York: Harper and Row

Milgram, S. (2005). The perils of obedience. POLIS, Latin American Review.

Milgram, S., Goitia, J. de, & Bruner, J. (2016). Obedience to Authority: the Milgram experiment. Captain Swing.

Shanab, ME, & Yahya, KA (1978). A cross-cultural study of obedience. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society .

Smith, PB, & Bond, MH (1998). Social psychology across cultures (2nd Edition) . Prentice Hall.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behavior. Social Science Information, 13 , 65-93.

Zimbardo, PG (2012). The Lucifer Effect: Do You Become Bad?