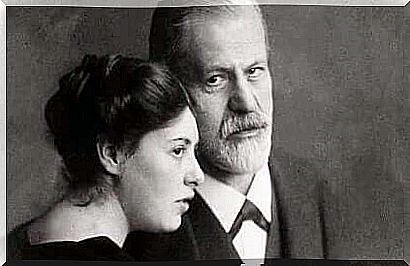

Sophie Freud, Sigmund’s Lost Daughter

When Sophie Freud died, her father was forced to change many of his theories on bereavement. He realized that that pain, that emptiness, would never go away. It would weaken over time, but he would never forget it. He also understood that there were no shelters in which to alleviate suffering, because the death of a child, he said, is inconceivable.

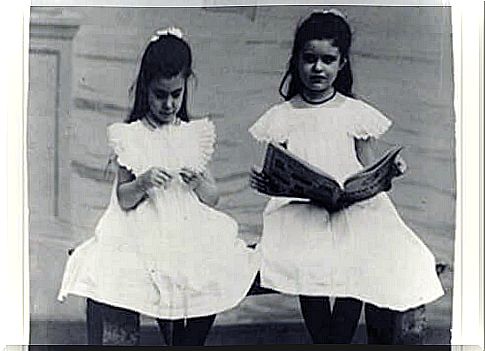

Sophie Freud was the fifth daughter of Sigmund Freud and Sophie Halberstadt. She was born on April 12, 1893 and almost immediately became her father’s favorite. That little girl succeeded, no one knows how, in softening the tyrannical and patriarchal character of the father of psychoanalysis. She was beautiful, stubborn, and determined to follow her will beyond what her environment determined.

At the age of 20 she married Max Halberstadt, a photographer and portraitist from Hamburg. The thirty-year-old boy was neither rich nor well known or promising. Freud knew that his daughter would encounter difficulties, but he did not oppose their bond. He just made her promise to keep him updated in case of any problems or concerns.

Young Sophie kept her promise. No one could foresee that the happiness of Freud’s favorite would last so short. He died only six years after the start of the marriage.

The first years of marriage

A year after the marriage of Sophie and Max Halberstadt, Ernst Wolfgang was born. Sigmund Freud was fascinated by that child, as he told in a letter sent to his colleague Karl Abraham:

Recall that the Second World War was already raging in Europe. Sigmund Freud was one of the first figures to warn of that disconcerting and brutal thought that was also sprouting in Vienna, his hometown. His personal and family circle was not affected until Hitler’s rise to power in 1933.

Until then, Freud continued his work by continuing the exchange of letters with his daughter Sophie. On December 8, 1918, his second grandson, Heinz, was born. It was then that the young woman confessed her financial problems to her father, and that the arrival of the second child was a blessing, but also a problem.

Freud immediately offered her the help she needed. As we can read in Letters to the children, he also offered his daughter advice on birth control methods of the time. But it seemed to have no effect, because a year later Sophie got pregnant again.

The third unwanted pregnancy and the death of Sophie Freud

When Sophie wrote to her father dreadfully announcing the third unwanted pregnancy, he replied thus:

In 1920, Europe fell victim to Spanish fever and Sophie, debilitated by her third pregnancy, was hospitalized in January. He died a few days later of an infection. After the loss of his daughter, Sigmund Freud wrote about the repercussions this event had on him.

He explained that he had not been able to find a means of transportation to be near her in her final days. He could only go to the funeral and accept a loss that he could not make sense of or explain. The most surprising thing, however, happened nine years after that loss. In a letter he wrote to one of his best friends and colleagues, Ludwig Binswanger, he confessed that he still hasn’t gotten over his daughter’s death.

Sigmund Freud and mourning

In Letters to the Children we can also read the missives that Freud and Doctor Arthur Lippmann of the Hamburg hospital sent to each other after Sophie’s death, at the age of 26. The father of psychoanalysis disapproved of the fact that medicine still did not have effective methods of contraception.

In the letters, he also complained about what he called “a foolish and inhumane law that forced women to carry on unwanted pregnancies.”

After the loss of his daughter Sophie , Sigmund Freud tried to deal with the grief in his own way, and he prolonged it for more than ten years. He got to the point of having to reformulate this concept in his theories.

Finally, he had to accept that when faced with a loss, one can feel both sadness and melancholy, and that both moods are acceptable. Pain was also a challenge compatible with survival. It was (and is) that stubborn bond that we refuse to let go because it is a way to hold on to love for a loved one.